Note on versions:

- the paper linked at this website is a new version of the paper that is available on Arxiv (arxiv link)

- the main additions are experiments with more LLM models

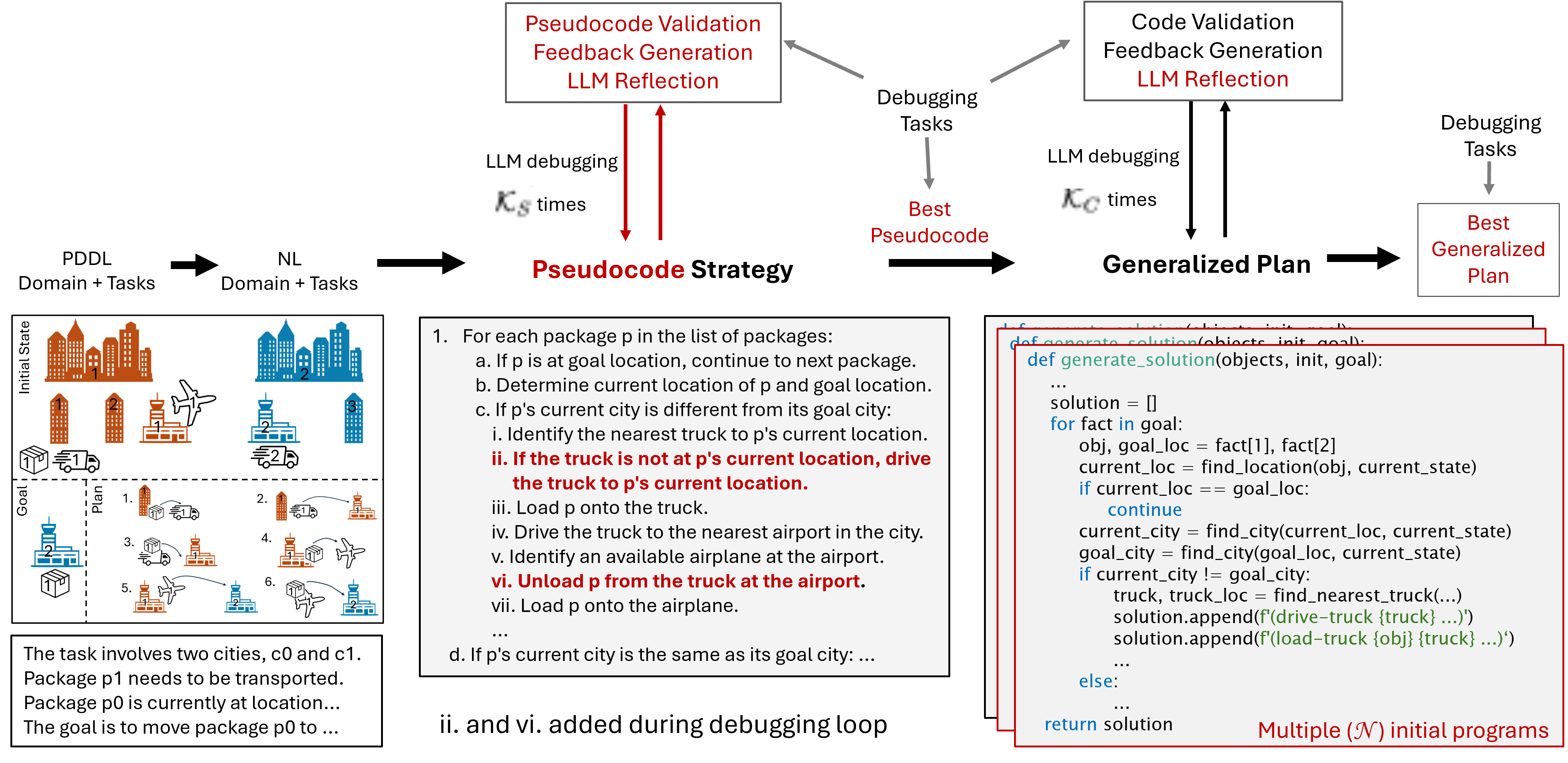

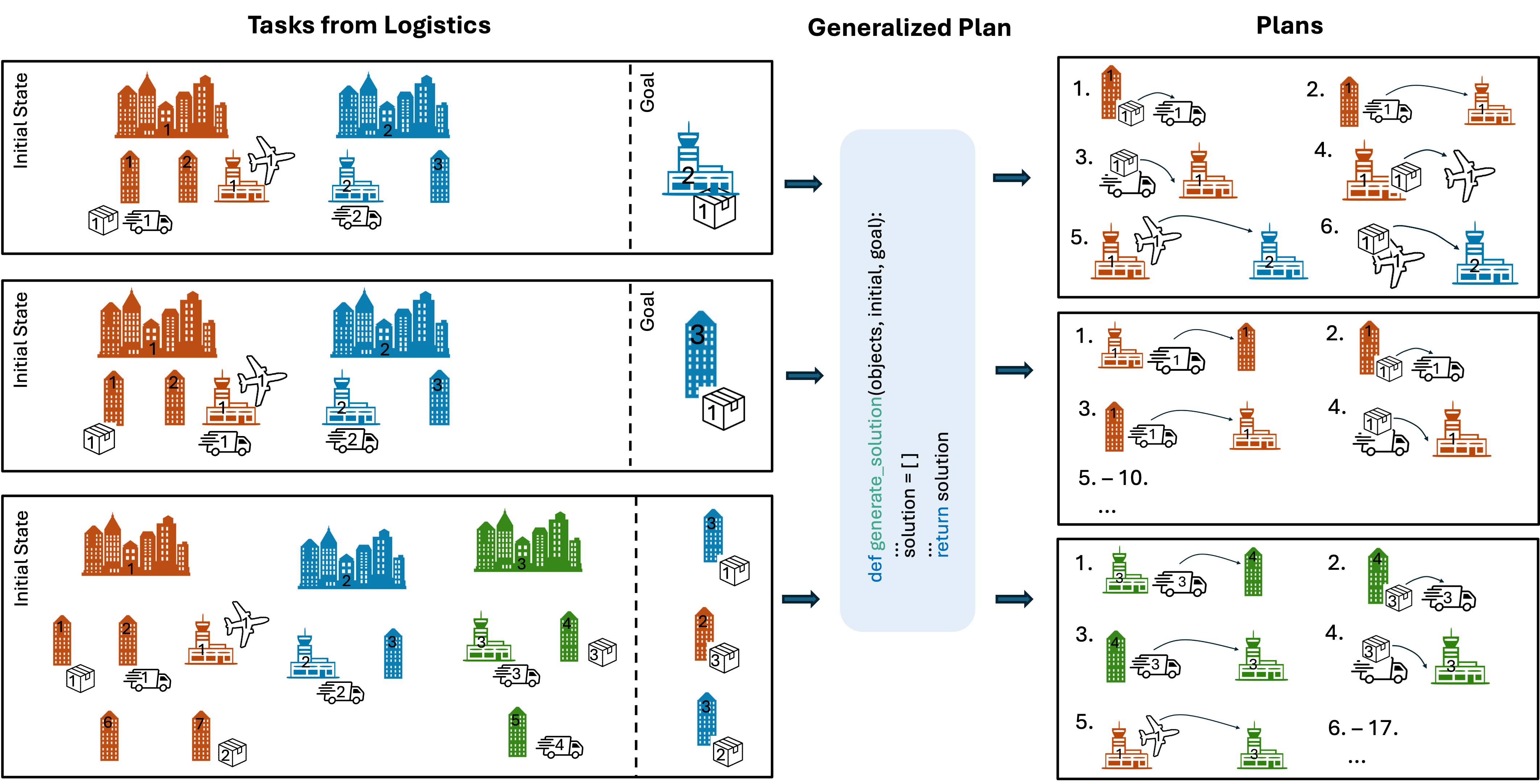

We introduce an approach for generating improved generalized plans in PDDL planning in the form of Python programs using LLMs. Generalized plans are plans that generalize across the tasks of a given PDDL domain.

For example, in the Logistics domain the goal is to transport packages from their initial location to their goal location using trucks and airplanes. A planning task from that has a specified number of cities each consisting of the same number of locations out of which one is an airport. A specified number of airplanes is randomly distributed across all airports. Each task also includes a specified number of trucks, such that there is at least one truck per city. A specified number of packages is distributed over all possible locations. The goal specifies for each package a goal location.

Our approach generates Python programs that can take any of such tasks from the Logistics domain as input and generates the corresponding plan, i.e. the sequence of actions required to transform the specific initial state into a state satisfying the goal constraints.

Overview

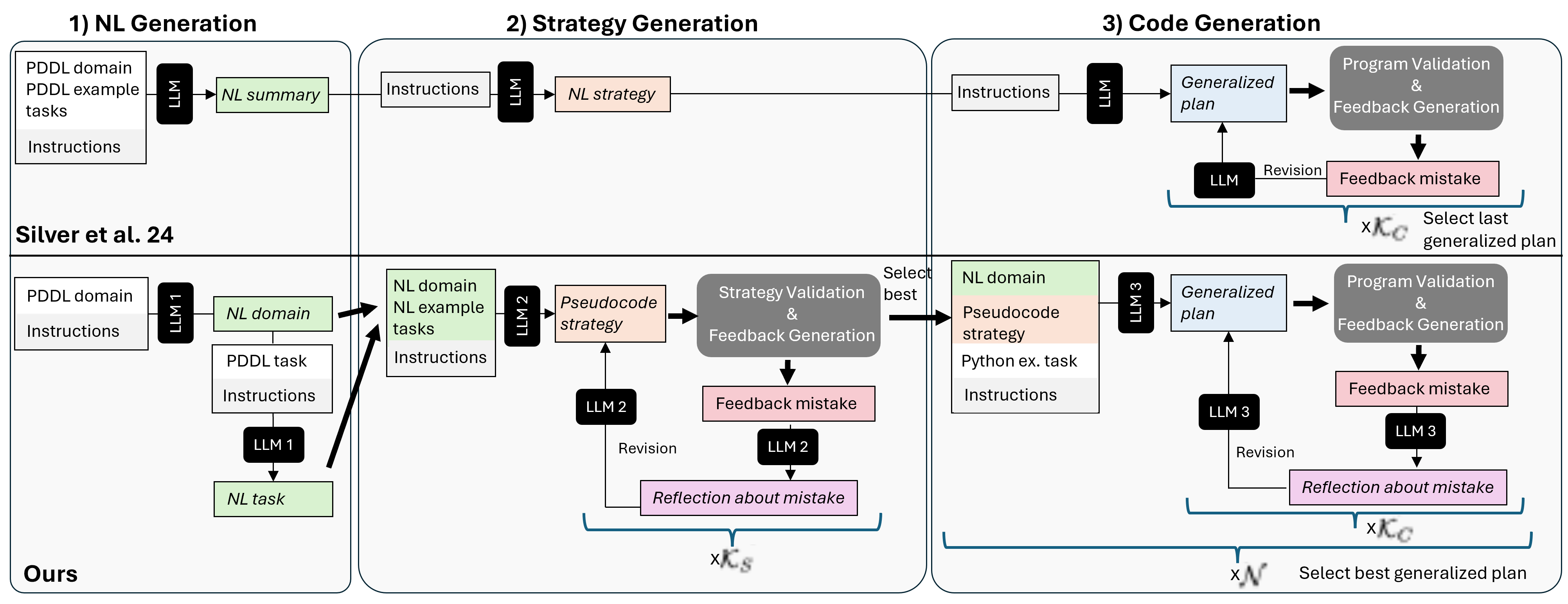

Previous work (Silver et al. ‘24’) proposed a framework consisting of three steps:

- the LLM first generates a summary of the domain in natural language,

- the LLM then generates a strategy for the domain, again in natural language, and

- the LLM then implements that strategy as a Python program, that gets debugged on example planning tasks.

In their work, only one strategy is generated and passed directly to the program generation. If the strategy is incorrect, its implementation will therefore result in an incorrect generalized plan.

Our contributions

- generation of strategies in the form of pseudocode.

- an approach to automatically debug the pseudocode.

This approach allows:

- to shift most of the work beyond the mere conversion into Python to the step preceding the code generation.

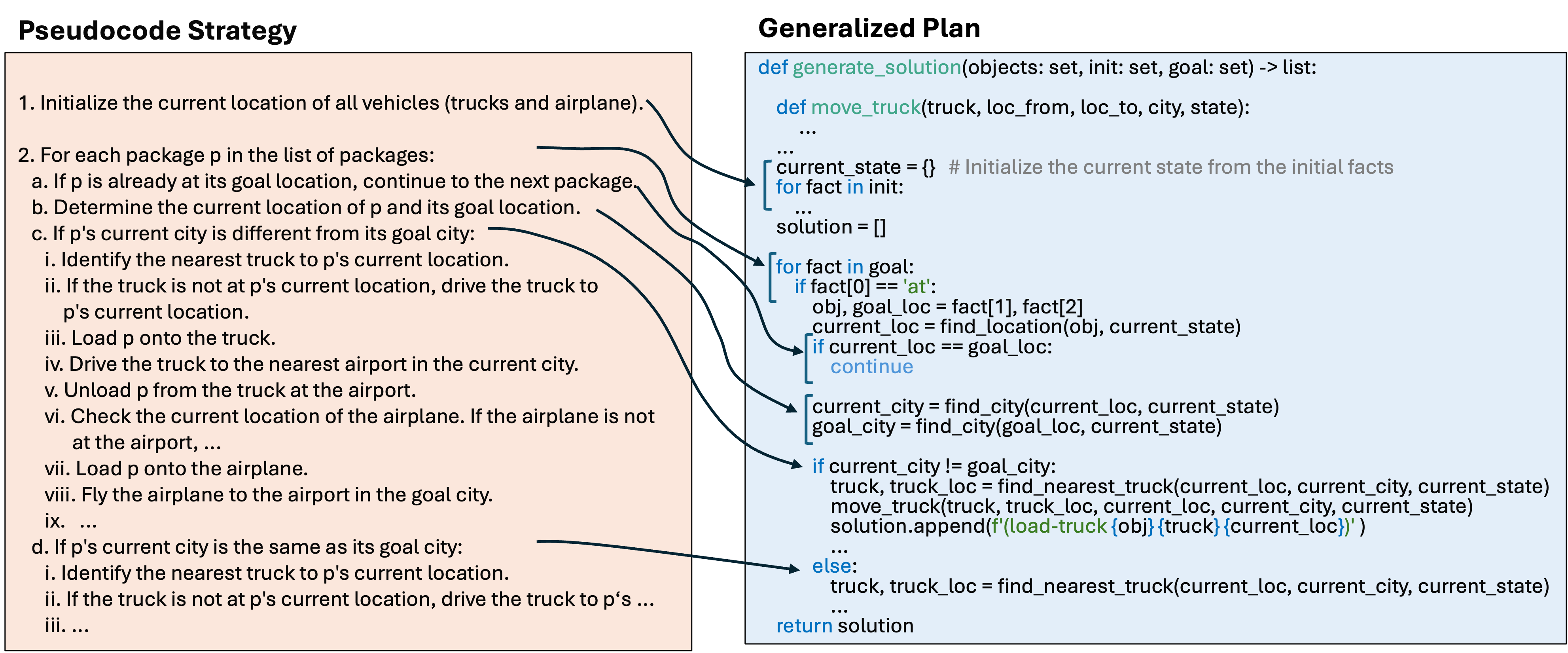

- intermediate form of the strategy is closer to the final target output, has a clearer structure and less ambiguity than NL strategies form previous work (see Figure below).

- to identify and fix errors in the strategy prior to the code generation.

- Additionally, we extend the Python debugging phase with a reflection step prompting the LLM to pinpoint the reason for the observed plan failure.

- We take inspiration from LLM code generation to produce several program variants and pick the best one.

Running experiments on 17 benchmark domains, we show that these extensions substantially improve (and never deteriorate) the quality of the generalized plans.

In 12 of the domains, our best Python programs solve all tasks that can be generated with the respective instance generator.

Our pipeline

The following Figure illustrates our full pipeline, also in comparison to the pipeline from Silver et al.

Below you can find examples of the most relevant steps with prompts and outputs for the Logistics domain.

Examples Logistics Domain

1. NL Generation

For the strategy validation approach, we provide the domain and debugging task in NL form. Therefore, we require a separate NL description for each debugging task. We obtain the NL descriptions in a two-step process: 1. First, the LLM is prompted to generate the NL domain description given the PDDL domain. 2. Afterwards, the NL description of each debugging task is generated based on its PDDL definition and the PDDL and NL domain descriptions.We also use that NL domain description and two debugging task descriptions as input for the pseudocode generation.

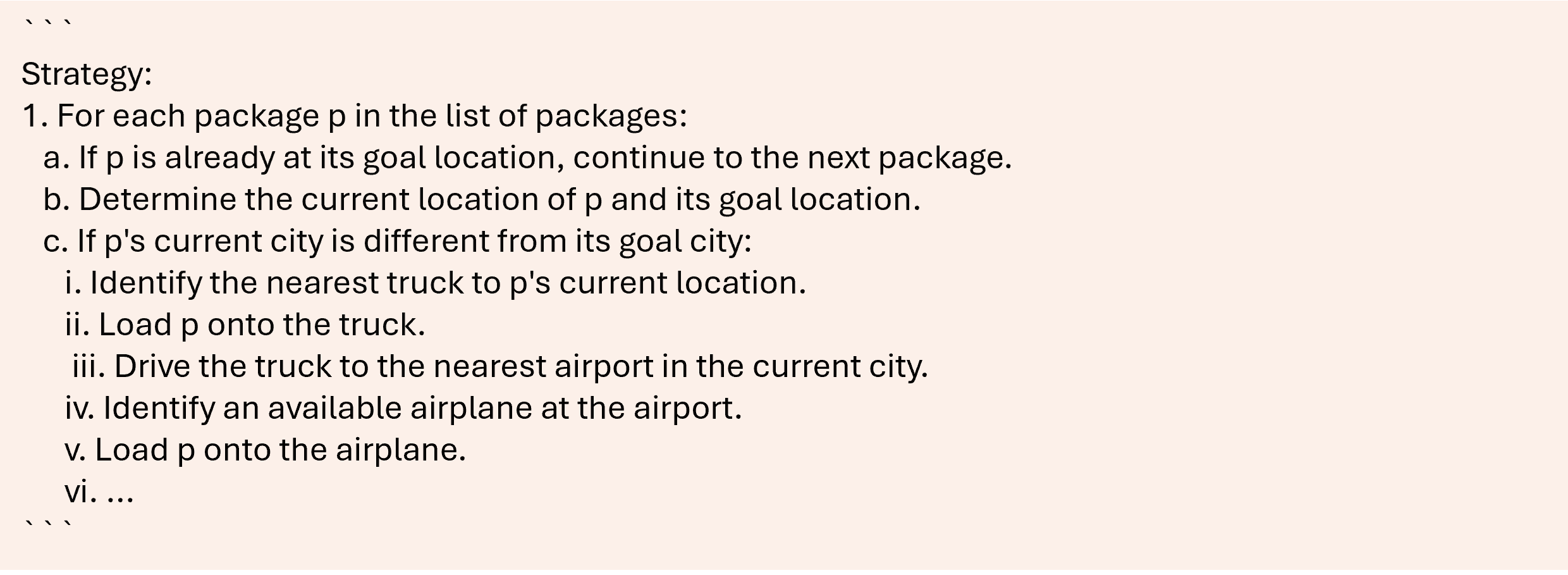

2.1 Strategy Generation: generating initial pseudocode

We instruct the LLM to generate the strategy in the form of pseudocode that should be detailed and specific enough to be converted into an executable program in a straightforward way. The prompt for this step consists of the NL descriptions of the domain and two example tasks and instructions to think step-by-step (zero-shot CoT, Kojima et al., 2022).Note: "..." indicates abbreviated content for better readability and is not part of the original prompt.

- Pseudocode Generation Prompt:

- Response of the LLM:

- Step-by-step outline of the strategy:

- Final strategy in the form of pseudocode:

- Step-by-step outline of the strategy:

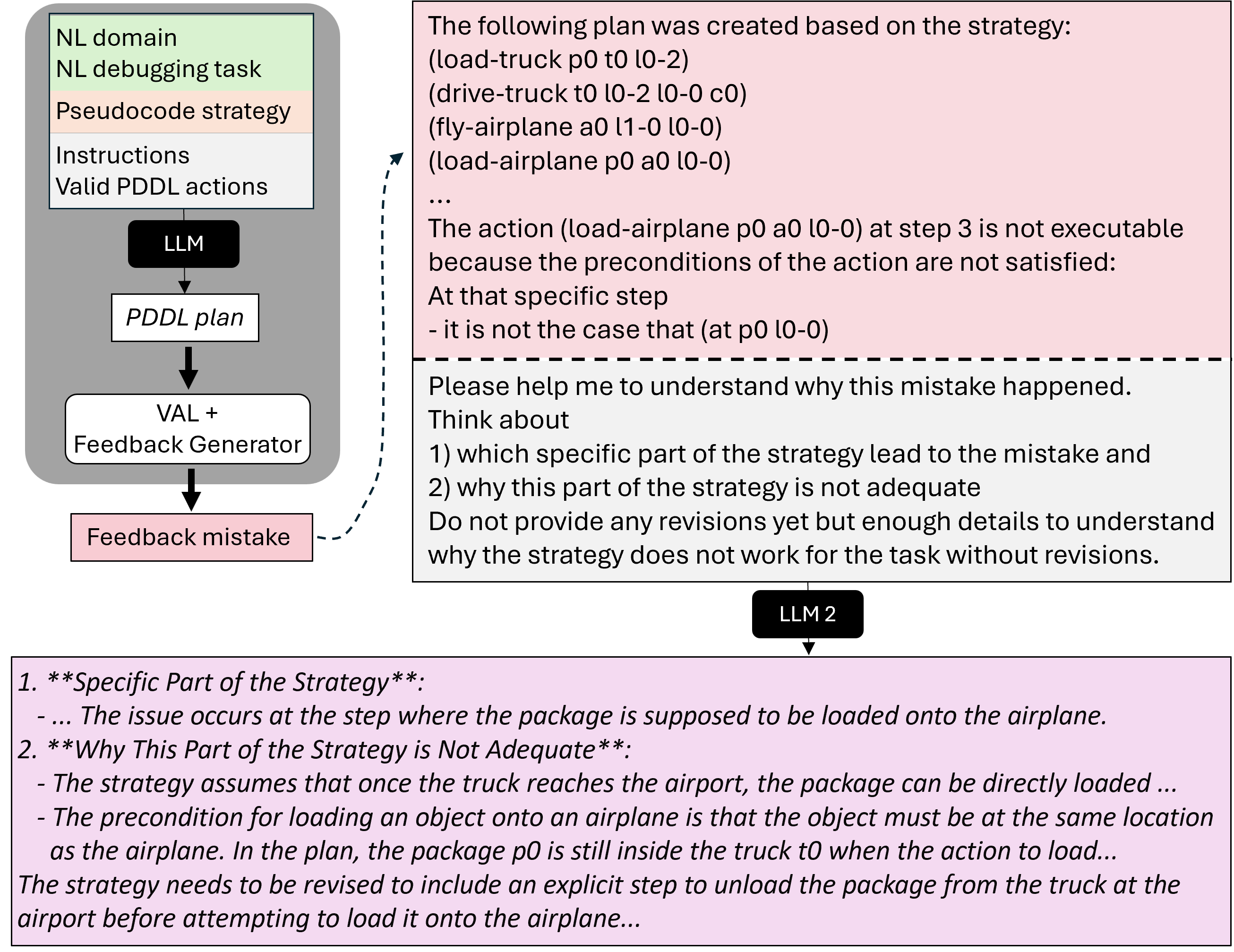

2.2 Strategy Generation: pseudocode debugging

- An LLM is prompted to generate the PDDL plan for a given debugging task (in NL) by following the strategy generated in the previous step. The generated plan is then validated using VAL.

- If the plan is incorrect, the validation output is converted into a feedback message about the mistake.

- The feedback is combined with the generated plan and instructions to reflect about the part of the pseudocode that caused the mistake and the reason why that part is incorrect (inspired by e.g. Madaan et al. 2023; Shinn et al. 2023).

- After generating the reflection response, the LLM is then asked to correct the pseudocode by thinking step-by-step.

- This process is continued until the LLM generates correct plans for all debugging tasks or a maximum number of debugging iterations, K_S, is reached.

- The pseudocode that resulted in the highest number of solved tasks is selected for the code generation step.

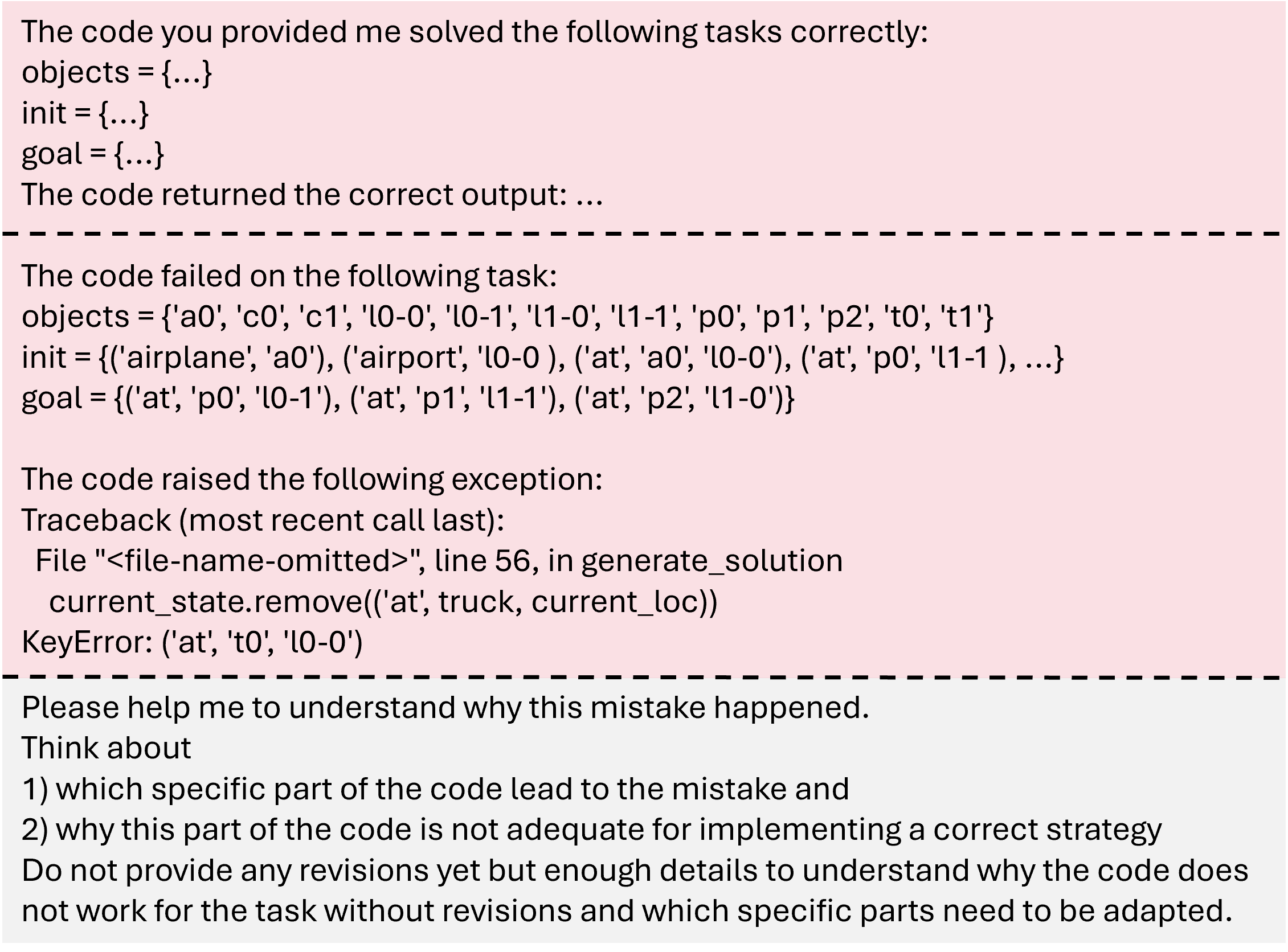

3. Code Generation

Last but not least, we prompt the LLM to provide python code that implements the generated pseudocode strategy given the NL description of the domain and the pseudocode strategy.- First Code Generation Prompt:

- Error Feedback and corresponding Reflection Prompt:

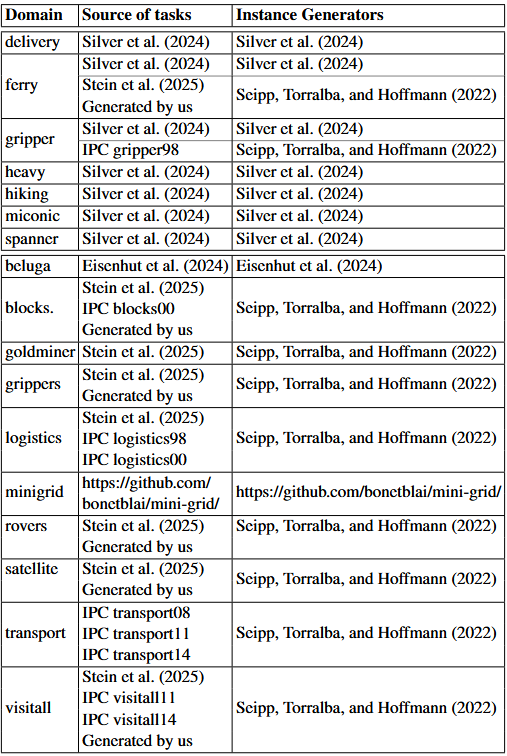

Data

For our experiments, we focus on domains that have previously been used in research on LLMs in the context of classical planning. In particular, we use the domains from Silver et al. (2024)’s generalized planning experiments and Stein et al. (2025)’s LLM action-choice experiments. Table 2 shows for each of the domains the sources of the tasks we include in our experiments. All tasks included in our experiments are solvable. The right column of Table 2 shows the origin of the instance generators that we used to generate additional tasks for some of the domains, and that we used for the manual evaluation of the generalization power of our generalized plans.

Table 2

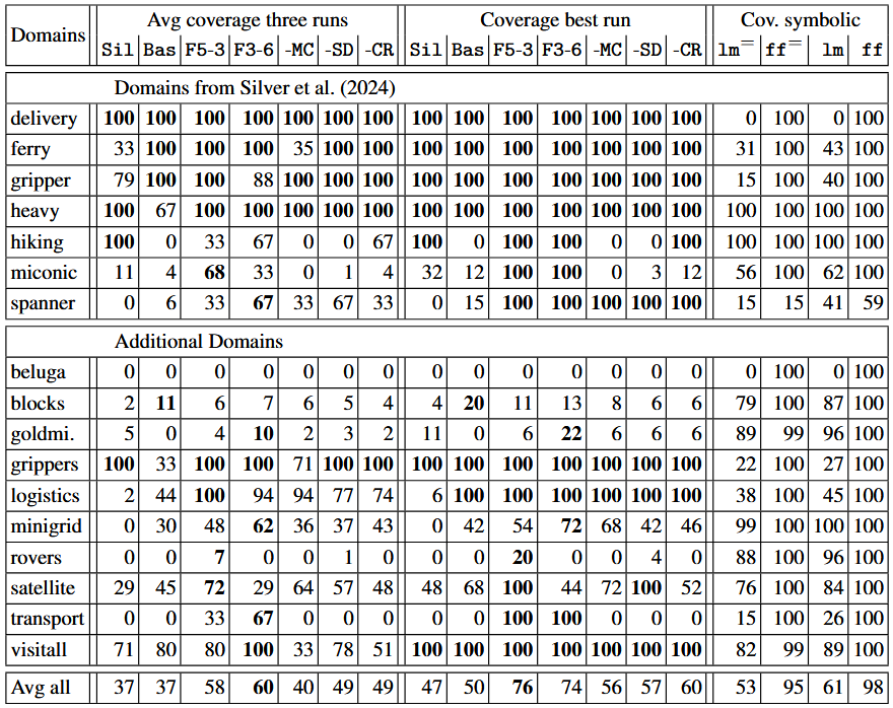

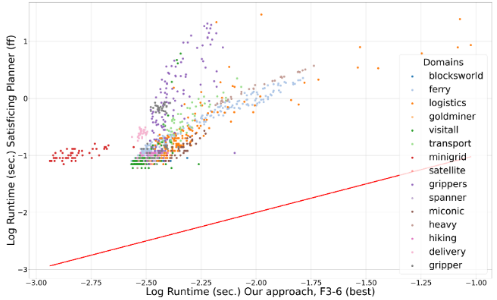

Experiments and Results

Evaluation

- Metric: Coverage - The percentage of evaluation tasks for which the Python program generates a correct plan.

- Average: The average coverage over all 3 runs.

- Best: The coverage of the best run.

- Time limit of 45 seconds for running the programs.

- Each program is ran 4 times with random ordering of ob objects and initial/goal facts and treated as correct if each ordering results in a correct plan.

- Final evaluation based on the best generated program as determined on the debugging data.

- For each configuration, we conducted 3 runs of the complete pipeline, each with a different pair of initial example tasks provided to the LLM.

Our Framework

We test our framework for two different combinations of the maximum number of initial programs (N ) and code debugging steps (KC ) and conduct three ablation experiments to assess the effect of our pipeline extensions.

We also compare the performance of our approach to 2 baselines.

The set-ups tested are the following:

| KS | N | KC | max. programs | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F3-6 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 21 | Our framework |

| F5-3 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 20 | Our framework |

| -MC | 6 | 1 | 6 | 21 | Ablation: effect of multiple init programs |

| -SD | 0 | 3 | 6 | 21 | Ablation: effect of strategy debugging |

| -CR | 6 | 3 | 6 | 21 | Ablation: effect of code reflection step |

| Sil | 0 | 1 | 6 | 7 | Silver et al. |

| Bas | 0 | 1 | 6 | 7 | Re-implementation of Silver et al. |

- Re-implementation of Silver et al., adapted for a fairer comparison:

- more similar phrasing of prompts, including instructions to think step-by-step for NL strategy generation.

- separation of the three parts of the pipeline.

- example task an failed task is provided in the Python format during code generation.

- selection of final program based on debugging data.

Symbolic Baselines

- lm: optimal A* and the LM-Cut heuristic (Helmert et al. 2009), ran with a 30-minute time limit.

- ff: satisficing greedy best-first search with FF heuristic (Hoffmann and Nebel, 2001), ran with a 30-minute time limit.

- ff= and lm=: Like lm and ff but with the same 45s time limit as applied to the execution of generalized plans.

Results:

References

More Detail

M. Helmert and C. Domshlak. Landmarks, critical paths and abstractions: What’s the difference anyway? In *Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling, ICAPS*. AAAI, 2009.J. Hoffmann and B. Nebel. The FF planning system: Fast plan generation through heuristic search. 'Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research*, 14:253–302, 2001.

K. Valmeekam, M. Marquez, A. Olmo, S. Sreedharan, and S. Kambhampati. Planbench: An extensible benchmark for evaluating large language models on planning and reasoning about change. In *Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track*, 2023.

K. Valmeekam, M. Marquez, S. Sreedharan, and S. Kambhampati. On the planning abilities of large language models - a critical investigation. In *Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems*, pages 75993– 76005. Curran Associates, Inc., 2023.

J. Wei, X. Wang, D. Schuurmans, M. Bosma, b. ichter, F. Xia, E. Chi, Q. V. Le, and D. Zhou. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In *Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems*, volume 35, pages 24824–24837. Curran Associates, Inc., 2022.

S. Yao, J. Zhao, D. Yu, N. Du, I. Shafran, K. R. Narasimhan, and Y. Cao. React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. In *The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations*, 2023.

Bonet, B.; Palacios, H.; and Geffner, H. 2009. Automatic Derivation of Memoryless Policies and Finite-State Controllers Using Classical Planners. Proceedings of the International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling, 19(1): 34–41.

Du, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, K.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.;Feng, J.; Sha, C.; Peng, X.; and Lou, Y. 2024. Evaluating Large Language Models in Class-Level Code Generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering, ICSE’24. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. ISBN 9798400702174.

Haslum, P.; Lipovetzky, N.; Magazzeni, D.; and Muise, C. 2019. An Introduction to the Planning Domain Definition Language. Synthesis Lectures on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 978-3-031-00456-8.

Helmert, M.; and Domshlak, C. 2009. Landmarks, Critical Paths and Abstractions: What’s the Difference Anyway? In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling, ICAPS. AAAI.

Hoffmann, J.; and Nebel, B. 2001. The FF Planning System: Fast Plan Generation Through Heuristic Search. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 14: 253–302.

Holtzman, A.; Buys, J.; Du, L.; Forbes, M.; and Choi, Y. 2020. The Curious Case of Neural Text Degeneration. arXiv:1904.09751.

Howey, R.; Long, D.; and Fox, M. 2004. VAL: Automatic Plan Validation, Continuous Effects and Mixed Initiative Planning Using PDDL. In 16th IEEE International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI 2004), 15-17 November 2004, Boca Raton, FL,USA, 294–301. IEEE Computer Society.

Jim´enez, S.; Segovia-Aguas, J.; and Jonsson, A. 2019. A review of generalized planning. The Knowledge Engineering Review, 34: e5.

Kambhampati, S.; Valmeekam, K.; Guan, L.; Verma, M.; Stechly, K.; Bhambri, S.; Saldyt, L. P.; and Murthy, A. B. 2024. Position: LLMs Can’t Plan, But Can Help Planning in LLM-Modulo Frameworks. In Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning.

Kojima, T.; Gu, S. S.; Reid, M.; Matsuo, Y.; and Iwasawa, Y. 2022. Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners. In Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave,D.; Cho, K.; and Oh, A., eds., Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 35, 22199–22213. Curran Associates, Inc.

Madaan, A.; Tandon, N.; Gupta, P.; Hallinan, S.; Gao, L.; Wiegreffe, S.; Alon, U.; Dziri, N.; Prabhumoye, S.; Yang, Y.; Gupta, S.; Majumder, B. P.; Hermann, K.; Welleck, S.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.; and Clark, P. 2023. Self-Refine: Iterative Refinement with Self-Feedback. In Oh, A.; Naumann, T.; Globerson, A.; Saenko, K.; Hardt, M.; and Levine, S., eds., Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 36, 46534–46594. Curran Associates, Inc. McDermott, D. M. 2000. The 1998 AI planning systems competition. AI magazine, 21(2): 35–35.

Seipp, J.; Torralba, ´A.; and Hoffmann, J. 2022. PDDL Generators. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6382173.

Shinn, N.; Cassano, F.; Gopinath, A.; Narasimhan, K.; and Yao, S. 2023. Reflexion: language agents with verbal reinforcement learning. In Oh, A.; Naumann, T.; Globerson, A.; Saenko, K.; Hardt, M.; and Levine, S., eds., Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 36, 8634–8652. Curran Associates, Inc.

Silver, T.; Dan, S.; Srinivas, K.; Tenenbaum, J. B.; Kaelbling, L.; and Katz, M. 2024. Generalized Planning in PDDL Domains with Pretrained Large Language Models. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 38(18): 20256–20264.

Srivastava, S.; Immerman, N.; and Zilberstein, S. 2011. A new representation and associated algorithms for generalized planning. Artif. Intell., 175(2): 615–647.

Stechly, K.; Valmeekam, K.; and Kambhampati, S. 2025. On the self-verification limitations of large language models on reasoning and planning tasks. In The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations.

Stein, K.; Fiˇser, D.; Hoffmann, J.; and Koller, A. 2025. Automating the Generation of Prompts for LLM-based Action Choice in PDDL Planning. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling (ICAPS’25).

Tang, H.; Hu, K.; Zhou, J. P.; Zhong, S.; Zheng, W.-L.; Si, X.; and Ellis, K. 2024. Code Repair with LLMs gives an Exploration-Exploitation Tradeoff. In Globerson, A.; Mackey, L.; Belgrave, D.; Fan, A.; Paquet, U.; Tomczak, J.; and Zhang, C., eds., Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 37, 117954–117996. Curran Associates, Inc.

Valmeekam, K.; Marquez, M.; Sreedharan, S.; and Kambhampati, S. 2023. On the Planning Abilities of Large Language Models - A Critical Investigation. In Oh, A.; Naumann, T.; Globerson, A.; Saenko, K.; Hardt, M.; and Levine, S., eds., Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 36, 75993–76005. Curran Associates, Inc. Wang, E.; Cassano, F.; Wu, C.; Bai, Y.; Song, W.; Nath, V.; Han, Z.; Hendryx, S.; Yue, S.; and Zhang, H. 2024. Planning In Natural Language Improves LLM Search For Code Generation. arXiv:2409.03733.

Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; ichter, b.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q. V.; and Zhou, D. 2022. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; and Oh, A., eds., Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 35, 24824–24837. Curran Associates, Inc.

</details>

BibTeX

@misc{stein2025improvedgeneralizedplanningllms,

title={Improved Generalized Planning with LLMs through Strategy Refinement and Reflection},

author={Katharina Stein and Nils Hodel and Daniel Fišer and Jörg Hoffmann and Michael Katz and Alexander Koller},

year={2025},

eprint={2508.13876},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.AI},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.13876},

}

}